4 out of 5 stars

By J.C. Correa

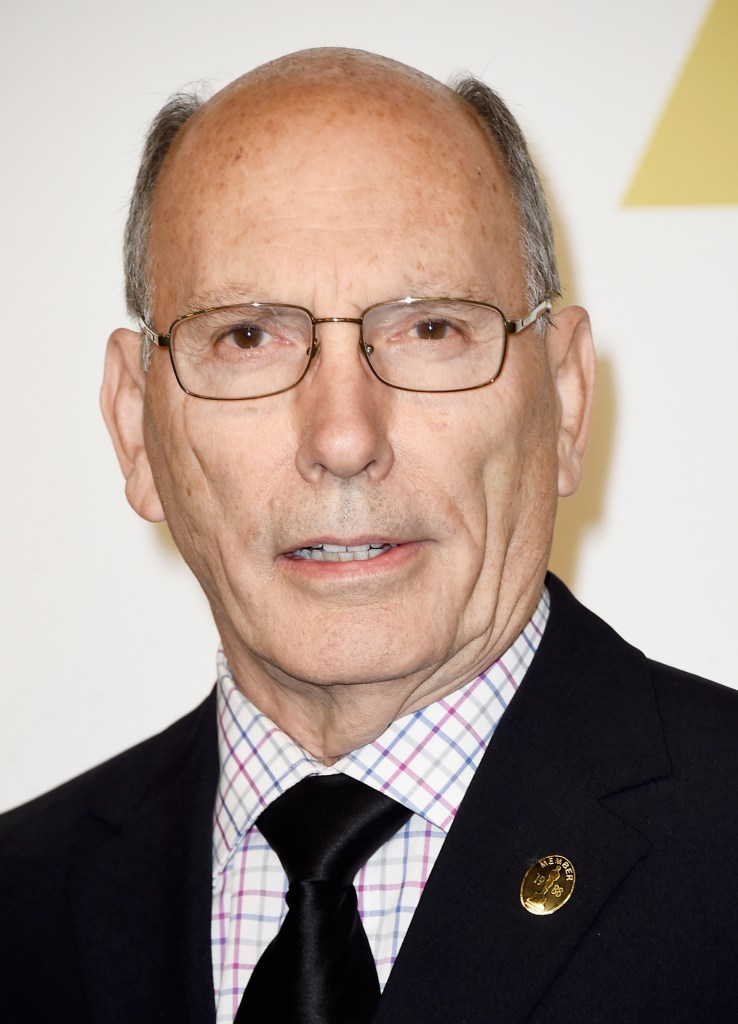

In 1992, after almost a decade away from the Western genre that initially made him a star, Clint Eastwood returned to it with Unforgiven and the Academy gifted him two Oscars for his efforts. They honored his work as both director and producer, as well as that of its editor, Joel Cox. For Best Supporting Actor, the fourth and final Academy Award that the film won went to Gene Hackman.

The movie was also quite popular with audiences, partly because it eschewed the established romanticized notions of the Old West, opting instead for a gritty realism that aimed for something thematically deeper. In doing so, this revisionist approach revitalized the genre and, along with Dances with Wolves two years earlier, helped usher it into a new phase of bankability at the box office.

Working off a script by David Webb Peoples (Blade Runner, 12 Monkeys), Eastwood clearly wanted to return to this terrain from an alternate perspective, and with entirely different things to say. Gone was the time-honored trope of the heroic, morally infallible cowboy, replaced instead by a repentant, aging gunslinger whose life is haunted by the many sins of his past. Former outlaw William Munny (Eastwood) is not only an antihero widower, but someone who has vehemently quit drinking and put aside his violent impulses and transgressive nature for the sake of his young children. A fitting substitute title could have been A History of Violence.

Even though he has firmly escaped from this life, Munny is drawn back into it by taking on a bounty that will help him support his kids. Said reward is offered by a group of prostitutes seeking justice against some cowboys who violently disfigured one of their brothel brethren, and who are protected by the town’s ruthless sheriff, Little Bill (Hackman). Munny enlists the help of his old friend in crime Ned (Morgan Freeman), and together they team up with an impetuous and loud-mouth wannabe triggerman (Jaimz Woolvett, looking like a young Heath Ledger) whose talk far outreaches his walk.

Like most Westerns, the pace is very slow, but in this case, it is frequently the result of the film’s meditative tone and introspective intent. For a movie that deals heavily with the emotional and psychological toll of violence, it’s surprisingly low on action, especially for a genre that’s famous for it. When it does occur, it’s usually perpetrated by Little Bill and executed with a savage brutality.

In Hackman’s case, the role awarded the venerable actor his second golden statue, twenty-one years after he first won it for a lead turn in The French Connection (both films he won for also went on to win the Oscar for Best Picture). Here, he eludes a quiet menace from the very first scene he appears in, with the character turning out to be his storied career’s most dastardly creation. Take for example how, after a tense standoff with English Bob (the late great Richard Harris in amusing and irreverent form), a former rival who has come to collect the bounty, Little Bill cashes in on his heavily secure position and viciously beats him in public to set an example. Later, after having poached the Brit’s biographer (Saul Rubinek) who is clearly in awe of him, he psychologically has his way with the naive man like a cat toying with a defenseless mouse, always asserting his dominance. Though there are other roles of his that I prefer and find more memorable, it’s impossible to deny Hackman’s precise execution of it, or the grim shadow he casts over the movie.

As such, this only works because he is pitted against someone as ruthless as Munny, who himself is played by someone as larger than life as Eastwood. The legendary actor-director does solid work in front of the camera as a tortured man reckoning with a past that cannot escape him. Despite even turning down free sex with one of the prostitutes, the fact that he’s eventually drawn back to his old way of life underscores one of the picture’s biggest themes: The inevitability of fate and destiny.

The cinematography by Jack N. Green is lush and often beautiful, and Eastwood frequently makes it a point to present strong images with rich compositions. The film actually opens with one of these: A beautiful, tranquil sunset setting over Munny’s peaceful and isolated farm. Although having the plot immediately cut to a scene of vicious violence depicting the brutal attack on the prostitute instantly establishes the aim. While there are visual nods to things like The Searchers, Western tropes are constantly deconstructed along the way and treated with utmost seriousness, existing solely in a very gray area that’s free of all humor and silliness. The subtle and unobtrusive score by Lennie Niehaus helps nicely in achieving this.

Everything eventually leads to the confrontation between Munny and Little Bill, which the movie has naturally been building towards. And though it is ripe with violence and bravado, the sequence also feels curiously lackluster and anticlimactic. Some audiences may have a gripe with that, and I would understand why, particularly in light of what is expected from the genre. However, it’s important to realize that the understated and simple nature of everything is precisely the whole point. The climax is not about Munny having a fancy showdown with Little Bill and his gang of deputies, but rather about Munny once again surrendering to his worst tendencies and thus setting his soul ablaze. There is a high cost to a life of violence that is not paid through blood or broken bones. It is no wonder then that Eastwood chooses to dedicate the picture to the two filmmakers who most taught him a thing or two on the matter – Sergio Leone and Don Siegel.

Nevertheless, I do wish the script could have done a better job in how it establishes Munny’s past as a murderous scoundrel. We keep hearing repeatedly what a bad man he was, even from his own account. But we never get to see it until the very end, and by that point, one could argue that he was simply nothing more than a gifted crack shot. Furthermore, we are denied the chance to feel the psychological effect that this late-hour violent purging has on him. I feel it would be a far richer movie had Eastwood chosen to explore that, rather than just have Munny exit like the baddest mother who ever came to town, while regressing him back into an archetype. I suppose doing it in the manner I suggest would partially undermine the trivialized nature of the piece. Alas, there’s a curse sometimes to wanting it both ways.

Unforgiven is available to stream on HBO Max.