3.5 out of 5 stars

By J.C. Correa

Originally released in 1973, Scarecrow is usually not the first movie that comes to mind when thinking about the filmographies of both Gene Hackman and Al Pacino. Part of this may have to do with the fact that it was a box-office bomb upon its release. And most of it is likely the result of the enviable breadth of the work of both iconic actors. But the film, directed by Jerry Schatzberg – who had already worked with Pacino a few years earlier on The Panic in Needle Park – is worth a second look.

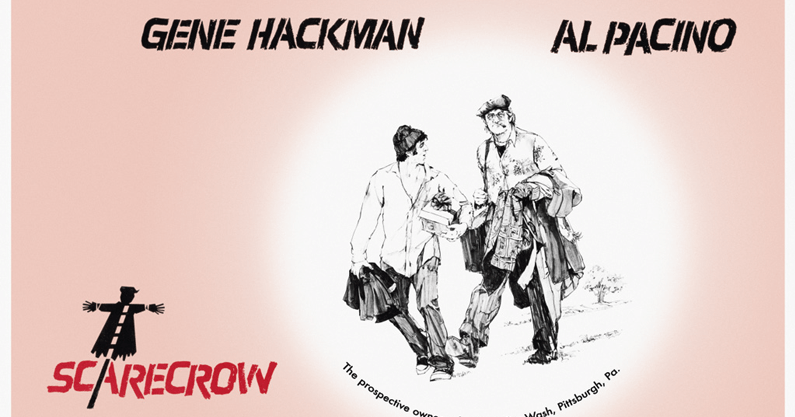

The story centers on the unlikely friendship between two drifters aiming to leave California and head east. Hackman plays Max, a quick-tempered ex-con who wants to get to Pittsburgh to open a car wash. Sporting John Lennon-type glasses that make him look a little smarter than he is, Max is always cold at any time of day, habitually wearing an excessive amount of layers of clothing. Lion (Pacino) is a goofy, childlike former sailor seeking to reconnect with the wife and child he left behind in Detroit. He enjoys breaking into spontaneous displays of tomfoolery, both to Max’s amusement and annoyance. Predictably, both men are set up as opposites, with Max as the hardheaded alpha, and Lion as the easygoing one. They meet while trying to hitchhike a deserted road, and the movie cleverly uses the amusing sight of them competing for a ride as a credits sequence. Acclaimed cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond contributes strong imagery here, and throughout the rest of the picture.

Before long, the film starts to evolve into a road movie/buddy comedy. The inspiration of Midnight Cowboy is clearly apparent (even as the tall, man’s man and short, scruffy sidekick gimmick is a little more bargain basement here), and from its occasional light touch and honky tonk-flavored score you can even assume that it may have served as some kind of blueprint for the decidedly lighter Midnight Run a decade and a half later. The two men first properly get to know each other at a diner, a scene in which Max propositions Lion to be his partner in his car wash scheme. It’s both ludicrous and sad to think that two complete strangers would casually agree to this after having only known each other for 15 minutes. And yet, in some strange way, you believe it, and a large part of that has to do with how convincingly both actors inhabit these two fellas who are not entirely all there. It’s also probably the reason why Schatzberg chose to shoot almost this entire scene in one uninterrupted take.

When not hitchhiking with anyone who will give them a lift, or frequently causing a ruckus at bars, the two men stop in Denver to spend some time with Max’s sister (Dorothy Tristan) and her friend Frenchy. The latter is played by Ann Wedgeworth, who essentially does another variation on the overly sexed-up schtick she brought to Three’s Company a few years later. In fact, I wouldn’t be surprised if the casting director from that television hit gave her the job simply on the strength of what she does here. During a KFC takeout dinner at home, Frenchy throws herself at Max in every way imaginable while he tries his best to keep a straight face and elaborate on his business idea to his sister and Lion. The reason the scene does not veer into absolute slapstick has exclusively to do with Hackman in how restrained he plays it all.

There is a powerful and disturbing moment later when a man (a creepy-looking Richard Lynch) suggestively propositions Lion for sex before outwardly begging him for it. He then tries to force himself on him after his advances are turned down, terminating in violent retaliation. The scene is very effective because of how gradually its tension builds, but also because both actors manage to make their individual plights in some way relatable at that exact moment. Schatzberg brings the camera close to all of it, creating a suffocating effect. Shortly afterwards, when Max gets retribution against the aggressor in the name of his friend, the violence is depicted through a single extreme long shot, far removed from everything, which gives it a matter-of-fact quality. The choices create an effective contrast.

In the tradition of buddy movies, there are ups, downs, developing friendships, resentments, makeups, and a whole lot of co-dependency. While both characters have their positive traits, they are also individually pathetic in their own way. This becomes more apparent as the story evolves, which also coincides with the grimmer tone that the film seems to veer into as it treads along. Though it’s clearly headed to a dark place – but not necessarily where you might expect – the tone itself is not always consistent, occasionally still feeling the need to keep things light in an otherwise bleak third act. I do see this as a flaw of the movie, though some might appreciate its attempts to let out the air.

What really makes the film watchable at the end of the day is the work of its two leads. For Pacino, it’s a quieter, more understated performance, at least in comparison to what we’ve become used to over the past 50 years. He brings a warm sweetness to the role that works very well in getting us to empathize with his plight and feel for him when life knocks the wind out of his sails. In Hackman’s case, the part plays into his tough-guy image, and allows him to unleash that signature mischievous chuckle of his, a lot. But he’s also a broken man in his own right, and in one memorable sequence, he playfully attempts a tame strip tease at a bar in order to bond with Lion. It’s a high point of the movie, and much like the opening shot of him getting caught on a fence and then falling into a ditch, it’s yet another reminder of how good Hackman was at comedy, and of the ample charisma he had to work with.

Scarecrow is available to rent on Fandango at Home.