3.5 out of 5 stars

By J.C. Correa

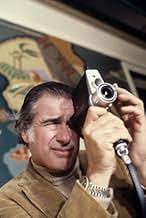

Across an illustrious and varied acting career that spanned over four decades, Gene Hackman’s most signature role (at least to anyone not raised solely on comic books) will undoubtedly always be Jimmy “Popeye” Doyle, the ruthless, morally-questionable New York City police detective that the venerable actor played to Oscar-winning glory in 1971’s The French Connection. While the film also won the Academy Award for Best Picture, launched Hackman’s career as a leading man, and is rightfully still considered one of the greatest cop thrillers of all time, for the sake of this retrospective, I thought it more interesting to instead revisit its oft-forgotten sequel, 1975’s French Connection II.

Helmed by John Frankenheimer, who replaced the original’s Oscar-winning director, William Friedkin, the second feature keeps the gritty, neo-noir action suspenser tone of its predecessor, but switches the tale from New York City to Marseille. Having been unable to capture elusive drug kingpin Alain Charnier (a returning Fernando Rey) at the end of the first movie, Doyle is sent to the French city by his superiors on account of being the only person who can identify Charnier, and thus, try at all costs to bring him down. A fish out of water in every capacity, Popeye establishes a tense and volatile partnership with English-speaking Inspector Henri Barthélémy (Bernard Fresson), who shares Doyle’s desire to bust the drug ring, in spite of his clear contempt for the American’s methods.

In the middle of this, however, Popeye is kidnapped by Charnier and his goons and is soon injected with copious amounts of heroin to quickly turn him into an addict. It is enough to suddenly render his pursuit of them utterly trivial and inconsequential. After practically leaving him for dead, the strung-out cop is slowly brought back to life by Barthélémy and his squad. Step by excruciating step, Doyle has to rely on his grit and willpower to fully kick the habit and get himself back to a reasonable state of health in order to continue his perilous mission.

If you have never seen the film, yet are somehow familiar with the original, you can surmise that, while they share genre and overall style, things do differ significantly when it comes to the specific arc that Doyle undergoes in the second picture. As a human being, Popeye is reprehensible for a lot of reasons: he is a racist, a bully, and an alcoholic. He constantly displays temper tantrums and throws his weight around every chance he gets. He never misses the opportunity to show his air of superiority around the other French policemen, whom he clearly has much disdain for. Hackman plays Doyle almost like a dog: frequently showing his teeth and constantly barking orders. It is perhaps not entirely an accident then that a random canine is seen running down a hallway as Popeye chases Charnier during the same in one of the later scenes.

Hackman is as committed to the character in this feature as he was the first time around. He exhibits Popeye’s brash intensity from the very opening scene, which sees him arrive ill-tempered at a fish market in Marseille (the metaphor for the fish-out-of-water story that follows is not too subtle). This behavior instantly connects him to how he played the part in Friedkin’s movie. There is even an early, direct recall to his famous line about “picking your feet in Poughkeepsie” that, while amusing, is not entirely necessary. However, the bizarre choice to wear Hawaiian shirts with his suits not only underscores the theme of displacement and scorn he feels for the locals but also sets him apart from the version we have previously seen. Hackman was as effectively skilled at playing heroic as the other way around. The script, written by Robert and Laurie Dillon with Alexander Jacobs, allows him to do just that, despite all of Doyle’s dastardly traits. When we see him subjected to the heroin intake, Popeye accepts it all with a cunning bravado that feels absolutely right for the role, and you genuinely feel for him when he has to undergo the hellacious experience of withdrawal and the desperate mental and physical state it all plunges him into.

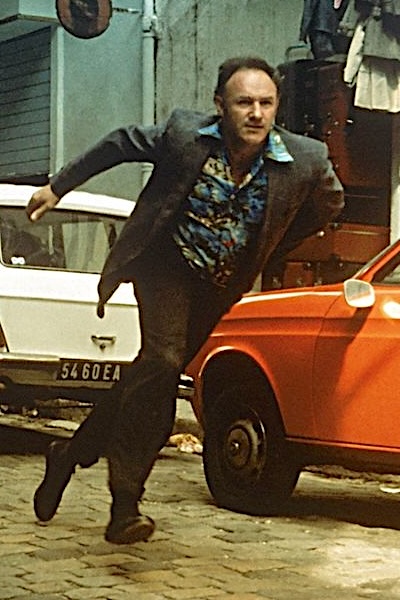

Frankenheimer was a good filmmaker in his own right, and smart enough to know that the prospect of Hackman reprising the role of Doyle was one best captured through long, steady takes that simply stayed on the actor and let him work his magic. Elsewhere, frequently employing a handheld approach that feels correct for the material, and knowing he has to make a genre picture that is also following up a beloved property, the director stages a few good set pieces in the form of various shootouts, a scene in which Popeye sets fire to a building (with Don Ellis’ cool, percussive jazz score pushing it along), and a street chase near the very end that sees Doyle push himself to his physical limit in order to catch Charnier. While the latter doesn’t reach the visceral heights of the original’s iconic car chase, the sequence is shot and edited with great efficiency all the same, and is easily one of the standout moments of the movie in terms of not just its construction, but also its bleak desperation and eventual resolution.

And yet, in spite of its generous servings of derring-do, the film will almost certainly be first remembered for its haunting and jarring middle act. It is a common action movie trope to have the hero captured midway through and tortured by the villain until he or she escapes or is rescued. And while French Connection II complies with that structure, what sets it apart is the radical nature of what the protagonist is put through; in this case, forced into a brutal addiction. Taking into account that the very thing that Doyle is trying to eradicate is directly used against him as a weapon, there is an undeniable cynicism to the whole thing. It is probably also the reason why, for most film buffs, the shorthand description of the first flick usually revolves around the car chase, whereas the second’s is the one where Popeye becomes a heroin addict. While this does shortchange the movie (in both cases), the nature of that entire, extended chapter does make this particular perception rather understandable.

A frequent criticism of this is that the heroin section halts the momentum of an otherwise engaging cop story. It is hard to argue against this because the simple fact is that the movie basically takes such a sharp left turn when this happens that it suddenly becomes an entirely different film. At least for a while. It is not until forty or so minutes later that it reverts back to being a police thriller. And though the middle section functions as a narrative outlier of sorts, its jolting nature is partially justified by what it offers Hackman as an actor. He is tasked with turning the abrasive, larger-than-life Doyle into a pathetic shell of himself, but never wasting the occasional chance to let us peek into whatever is left of the man’s inner fire. He does outstanding work along the way, and in this regard, I would not be surprised if fans of The French Connection feel less rewarded by the sequel than viewers who are simply admirers of Hackman’s craft.

By embracing this bait-and-switch approach, Hackman is given the chance to create a compelling character study around addiction, determination and desperation (the latter perhaps being the film’s most prevalent theme). This thoroughly gifted performer makes you feel the pain at every instance, relying on the character’s forceful nature to ensure it all lands even harder. He plays all of this incredibly well during a grueling restraining sequence in which the French police team aims to break Doyle down only to save his life. Shortly afterwards, in the flick’s most memorable scene, a heavily withdrawing Popeye bitterly tells a clueless Barthélémy that he almost made it as a player on the New York Yankees were it not for Mickey Mantle. The hysterical ramblings that ensue after this admission make him come across as a broken child, and Hackman tackles it all so brilliantly and naturally that the anger and pitifulness cut through with searing precision. It is a terrific scene, made even better by the fact that Frankenheimer chooses to just stay on his star throughout from mostly a single angle.

Inevitably, part of what makes French Connection II an inferior follow up to a classic are plot points that are inexplicably left unanswered or simply lack much logic from a screenwriting standpoint. Chief among these is the fact that Charnier lets Doyle live after turning him into an addict. While one can argue that this was certainly a cruel way to punish his nemesis, it is hard to believe that the act of eliminating him completely would not be a criminal’s safer way to go. Before all of that, when Charnier’s goons kidnap Popeye they inexplicably leave his gun on the street. After three weeks in captivity, Doyle is then released by them and looks mostly clean shaven. I seriously doubt that heavies of this nature would concern themselves that much with his appearance. And under what legal logic would Popeye even be allowed to go and investigate in France? It eventually becomes clear that the French cops are using him for their own purposes, but it is still quite difficult to believe that they would so freely hand over their jurisdiction to a man of his reputation.

I do recommend the movie, especially to those who genuinely appreciate the gift that Hackman had as an actor. There is certainly much to chew on there, as it is a performance that is absolutely worth revisiting or discovering anew. I would even go as far as saying that his work here is on par with what he did the first time he embodied Doyle and rightfully won an Oscar for. It is just a shame that the overall package, while competent, does not measure up to the excellent standard or iconic status of its predecessor.

French Connection II is available to rent on Fandango at Home.