3.5 out of 5 stars

By J.C. Correa

A burning cross is one of the most powerful and frightening images ever unleashed upon citizens of the United States. It is a searing blemish on the nation’s conscience, created by those who are so driven by hate that they are willing to desecrate the most sacred image of a theology they supposedly believe in, all in the name of division, intimidation, and supremacy. There are many of these crosses, as well as a handful of scorched homes, to be found in Alan Parker’s Mississippi Burning, a drama/crime thriller starring Gene Hackman and Willem Dafoe as two FBI agents investigating the disappearance of three civil rights workers in the Deep South in 1964.

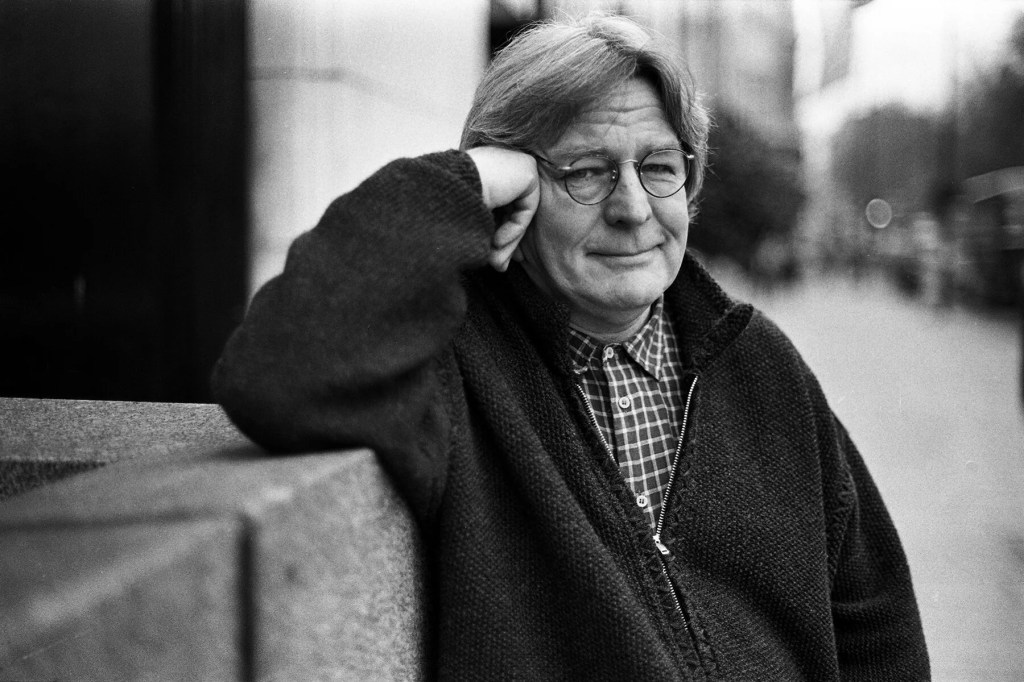

Portraying Agent Rupert Anderson, Hackman, in one of his five Academy Award-nominated turns, leads a solid cast that, apart from Dafoe, includes Frances McDormand, Brad Dourif, R. Lee Ermey, Michael Rooker, and Stephen Tobolowsky. McDormand was also Oscar-nominated for playing the sensuous wife of the local sheriff’s scummy head deputy (Dourif), who also takes a mutual liking to Anderson.

Originally released in the winter of 1988, the movie tells the partially true account of the murder of three civil rights workers (two Jewish, one Black) at the hands of the Ku Klux Klan in the fictionalized county of Jessup, Mississippi. Government Agents Anderson and Ward are assigned to the inquiry, and as is often the case in these pictures, their personalities and methods could not be further apart, and the film intentionally positions them as opposites. Though substantially younger than his partner, Ward is the senior officer, reliant on a stoic and methodical demeanor. Dafoe plays this very well against Hackman’s more carefree and approachable emissary; one whose former position as a Mississippi sheriff not only entrenches him much more easily into Southern sensibilities and ideologies, but also hints at the fact that, to some small extent at least, he might even share them, as evidenced by how he playfully sings a song about the Klan in an early scene.

It is pretty clear from the onset that Ward is the more righteous of the two; a point that is only underscored by a behavior thoroughly at odds with all of his surroundings, one informed by his Northerner status. Conversely, in spite of his ample charisma and fondness for a tiny necktie that makes him look disarming – if not outright comical – Anderson roams around a grayer moral area, often making us unsure if he is a rascal with a heart of gold and the ability to do the right thing, or a reprobate too settled in his ways. It is not one of Hackman’s flashiest roles and it is far from his most iconic, but what he delivers here is a tricky balancing act around an arc that eventually sees a man of questionable morality become downright heroic when there is no other option left. When Anderson grabs a despicable Klansman (Rooker) by the testicles to prove a point, or intentionally breaks into a barber shop to give the abhorrent deputy a bloody shave before beating the crap out of him in retaliation for his transgressions, it is easy for us to get behind his tough-as-nails ways.

Perhaps it is no coincidence that a similar effect is achieved in an earlier scene in which a nondescript Black man threatens to castrate the county’s corrupt mayor (Ermey), after the latter has been kidnapped and held as a sitting duck for a tormentor who begins by waxing poetic about the limitless possibilities of a razor. Considering the horrors that have been executed on African Americans in the South throughout more years in the country’s history than we care to remember, it is understandable that witnessing all of this provides a kind of cathartic, even if gruesome, relief. With regards to the torture and punishment inflicted on the innocent, Parker, working off a script by Chris Gerolmo, does not hold back in what he shows us, and his intention to disturb is clear. The scene of a young Black boy trying to rescue his father after he has been hung by Klansmen is particularly heartbreaking.

The vast array of burning landscapes that I previously referenced are undoubtedly an extension of that intent, and they are captured for the appropriately-titled film in an indelible way by cinematographer Peter Biziou, who won an Oscar for his work on it. The image of suited men traipsing waist-deep through a swamp in search of the bodies of the victims is another powerful one in terms of both its meaning and visual depiction. But perhaps heaviest of all are scenes in which newsmen interview local White residents about their opinions of Blacks, receiving answers that are often cringeworthy in their dehumanizing, barbaric nature. After rejecting all groups different to his, an affluent businessman (Tobolowsky) unapologetically declares, “We’re here to protect Anglo-Saxon democracy and the American way.” Sadly, that statement hits home in 2025 with as much force as it did in the mid ‘60s.

Parker frequently relies on tense, synth-driven music to remind us that we are watching a crime thriller more so than a historical account. While composer Trevor Jones’ contributions are effective enough to execute that first objective, they, nonetheless, are now fairly dated by their sound. I also posit that the movie would be stronger overall if it had more readily abandoned its sensationalist leanings and manipulative tendencies in exchange for a colder, more objective depiction of a particular time and place by simply just trusting the facts behind the drama. They are brutal enough to not require more.

Smartly, however, the production makes the most of a well-rounded cast that is more than up to snuff. And this actually starts on the casting level. Dourif, for example, with his crazy stare that immediately hints at some kind of perturbance, fits like a glove in the role of the sleazy deputy. In fact, a particular scene stands out as an example of how rich Parker’s options were in terms of which way to bank with regards to his actors. When Ward and Anderson go to the deputy’s house to interrogate him, one would think that this vital exchange is what the audience needs to see. Instead, upon arriving, Ward and the deputy have their dialogue in the background and mostly off camera, while the scene interestingly stays with Anderson and the deputy’s wife, allowing them to further establish their connection. Not only is this a major asset to the story, but when you have someone like Hackman and McDormand at your disposal it would almost feel like a disservice to not want to focus on them. Having Anderson be forcefully charming with her and try to cheerfully downplay the fact that his wife left him also gives Hackman wonderful stuff to play with. And, as always, what he gives to the scene is significantly more than what is on the page.

Mississippi Burning is available to stream on Amazon Prime.