The Last Showgirl

2.5 out of 5 stars

By J.C. Correa

During awards season six months ago, much was made about Pamela Anderson’s acclaimed performance in The Last Showgirl receiving Golden Globe and SAG nominations, yet getting completely ignored by the Academy come Oscar time. After finally watching the movie, almost a year after it premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival, I can understand it both ways.

The Last Showgirl is a drama directed by Gia Coppola (granddaughter of Francis Ford) and written by Kate Gersten, who adapted it from her own play Body of Work. It focuses on an aging Las Vegas showgirl named Shelly (Anderson) who is soon to be out of work; a reality that makes her reevaluate her own life and the dubious choices that made her prioritize her career over Hannah (Billie Lourd), the daughter she is now estranged from. The feature aims to examine the struggle that older women face in an industry that is primarily reliant on the commodity of youth and beauty. This point is addressed right out of the gate as the movie opens with an audition scene which sees Shelly lying about her age, twice, in an absurd fashion.

For three decades Shelly has been performing in an old-fashioned cabaret show called Le Razzle Dazzle. Now in her late 50s, she is the proverbial mother hen to most of the other dancers, all of whom are significantly younger. Her best friend is Annette, a one-time showgirl of Shelly’s generation who now barely gets by as a cocktail waitress. Annette is played by a scene-stealing Jamie Lee Curtis who, with her exaggeratedly-aged, leather-like tanned skin, is at times almost unrecognizable. Shelly also has a friendly relationship with the show’s manager, a meek and easygoing fellow named Eddie (Dave Bautista with a full head of hair that makes him pass for Lou Diamond Phillips).

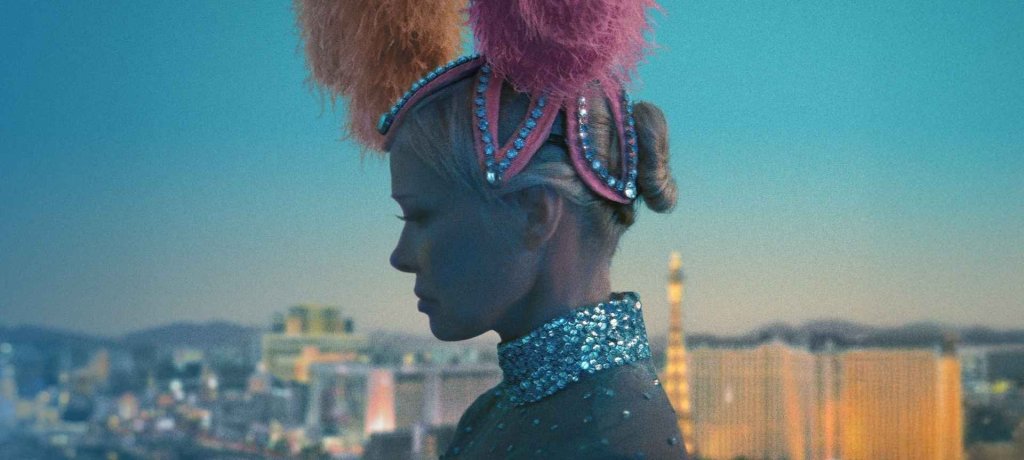

Coppola establishes early on that these characters exist far from Sin City’s prime time, as evidenced by a shot that shows them on a hotel rooftop that is actually not on the Strip, but rather, behind it. Similarly, she has chosen to shoot the picture in 16mm film stock, which allows for the anamorphic presentation to frequently have its images blurred along the edges. It is clear that the director is placing her focus on the emotion at center frame, while visually establishing the chaos of the world around its orbit. In this regard, the effect is mostly successful.

Undoubtedly, the movie’s biggest strengths are its performances; be it Curtis’ dazzling work, Lourd’s soulful and all-too-human presence, or Bautista’s quiet acting (whose impact lands even harder by virtue of the actor’s physical size). And yet, you may be wondering why I haven’t yet highlighted Anderson. That is simply because the actress, while fine overall, doesn’t deliver the not-to-be-missed turn that you may be expecting. She certainly has a few standout scenes, namely the aforementioned audition (and its aftermath in both a parking lot and a dressing room), as well as a crushing sequence in which one of the younger dancers (Kiernan Shipka) goes to Shelly’s home in desperate need of guidance, only to be sternly turned away. Elsewhere, however, Anderson operates on a level that allows for histrionics to occasionally seep in, thus allowing some of the artifice to become exposed.

But the film’s greatest flaws actually lie in both its screenplay and the overall execution that results because of it. It is clear that Shelly is living paycheck to paycheck and just scraping by (a point that is hammered by the distress that a reduced payday causes her to experience), and yet, inexplicably, a Ford Mustang is seen parked in her driveway. While this could be interpreted as a clear sign of denial from a person who is desperately clinging on to her former status and a gloried past, the fact that it is in direct conflict with her current reality implies that Shelly is either more delusional than we initially thought, or just plain stupid. If Coppola wants us to believe the latter, then she’s not giving her much room for redemption.

After a few initially awkward and funny moments at a dinner date between Shelly and Eddie, a significant plot point is also revealed about Eddie’s past that we simply do not see coming. This would not be a problem were the script not asking us to invest in its repercussions; a point that is impossible to do after forcing it in so causally, so late in the game, and without any hint whatsoever or attempt to set it up beforehand.

The world that the picture depicts is a dark and unforgiving one where self-deceit and suffering are around every corner. That’s the plain truth. In this regard, it is most certainly worth exploring and getting one’s hands dirty in doing so. But Coppola doesn’t display the necessary courage to do just that, and the script is not developed enough to give her the tools to do so. As I watched The Last Showgirl, I couldn’t help but imagine how much this material could have benefited from a thoroughly hard and unflinching take. While I commend Coppola for trying, she could have gained a lot by giving herself a crash course beforehand in the works of Sean Baker or Darren Aronofsky.

The Last Showgirl is currently streaming on Hulu.