The Unexpected and Glorious Legacy of Cobra Kai

By J.C. Correa

When Cobra Kai first debuted back in the spring of 2018 – on what was then known as YouTube Red – you would have been forgiven for being extremely skeptical about its prospects in quality, not to mention longevity. After all, no one was really asking for what was essentially a sequel to The Karate Kid Part III, a film that most of us who grew up with The Karate Kid would rather soon forget. And the idea of having it be told from the perspective of a one-dimensional antagonist from the first movie certainly did not add to the appeal.

My reaction to learning about its development the previous summer was very similar to the one I had felt a few years earlier when I first learned that Rocky was about to have a spin-off called Creed. In short, we didn’t need this, and no one was asking for it either. Incredibly, and very much to my pleasant surprise, my feeling upon watching Cobra Kai for the first time was also identical to what transpired when Creed first unspooled in front of my eyes: This has no business being this good!

And yet, it was. They both were. Both properties had been miraculously, against all odds and logic, done right. It all somehow seemed very fitting, and I certainly appreciated the irony. After all, The Karate Kid, in so many ways, always had Rocky in its DNA. Aside from sharing a director (filmmaker John G. Avildsen also went on to direct both Karate Kid sequels as well as Rocky V), both films shared thematic similarities through their respective stories of Italian-American nobodies who prove themselves by way of sporting competitions. Furthermore, two little-known facts that also link the franchises have directly to do with songs. Recording artist Joe Esposito initially submitted the tune “You’re the Best” for use in Rocky III, only to have it rejected by Sylvester Stallone. As a result, it was then deferred to Avildsen who found a nice place for it in The Karate Kid. Bizarrely, three years later, Peter Cetera did the same thing with his song “Glory of Love,” though this time for Rocky IV. And once again, Stallone said no. As we all know by now, it was instead slotted into The Karate Kid Part II and went on to become a chart-topping hit in the process.

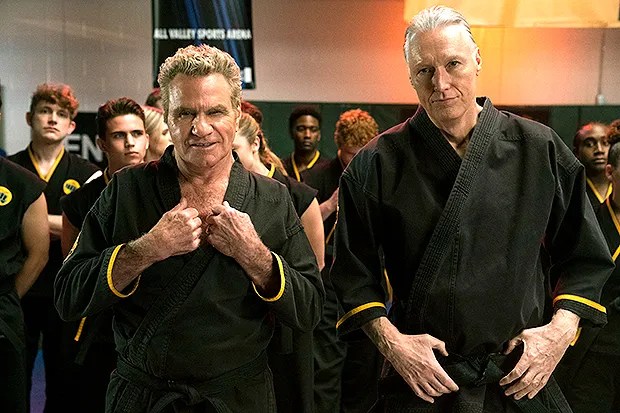

It is amusing, if not outright funny, that the Karate Kid franchise seems to have continuously inherited crumbs from Rocky. It is perhaps one of the reasons why many people have always thought of it as “Rocky-lite.” But that is not a dis, nor should it have to be. If anything, its brain trust has always embraced their shared heritage. And nowhere is this more evident than in the series finale of Cobra Kai that was just released last week on Netflix as part of a final batch of five episodes. Josh Heald, Jon Hurwitz and Hayden Schlossberg, the creators of the show, are probably more in tune with that fact that anyone else, and were clearly not afraid to admit it either, as evidenced by a few sequences from the finale that you might be forgiven for thinking were direct rip-offs of the Italian Stallion were they not such bona fide tributes to him.

It seems difficult to believe, but Cobra Kai not only succeeded in its shrewd experiment, but went on to last a full six seasons, all the while being picked up by streaming giant Netflix after its second season. Who could have imagined that so much mileage could be extracted by the simple idea of Johnny Lawrence never being able to get over his loss to underdog Daniel LaRusso in the All Valley Karate Tournament of 1984? After watching the charming and delightful first season, I must confess that I did not see it lasting more than two additional years. And yet, it managed to actually double that prediction to be exact. And it did it simply by consistently sticking to one exclusive mantra: Unapologetically treat the source material and its sequels as sacred texts worthy of absolute love and devotion.

There is a fine line between artistic honesty and fan service. Cobra Kai was filled with the latter on more occasions than anyone can count. But it never came across as such for the simple fact that you always got the sense that the filmmakers weren’t doing this for us as much as for themselves. In that regard, it is not inaccurate to say that the show was a passion project. Heald, Hurwitz and Schlossberg have always been very vocal about their full-on reverence for the movie they grew up with, and it showed in one form or another in each of the 65 episodes that comprise the series. After realizing they had a hit by successfully scraping every corner of the first movie’s mythology, they went on ahead and continued to build their franchise by tapping into the sequels with equal verve. Most fans of The Karate Kid rightfully have mixed feelings about the other two chapters, especially the much-maligned third one. And yet, if you love Cobra Kai, I suspect that you embraced all of the elements from each with the same enthusiasm as everything else. That does not mean that Cobra Kai has in any way made Part II and Part III better movies. What it has accomplished, though, is to retroactively make them more interesting, or at the very least, increase their importance.

One of Cobra Kai’s indisputable legacies will be to have brought Ralph Macchio, and particularly William Zabka, back into the pop culture limelight. I don’t think anyone could have necessarily imagined where the characters of Daniel LaRusso and Johnny Lawrence, respectively, would be as fifty-somethings. However, the one thing that did very much ring true from the onset was that neither of these former sworn enemies might be aching for a bromance upon first reacquainting decades later. The primary thrill of the series, bar none, was to see just how slowly, and in spite of innumerable obstacles, that bromance would eventually manifest.

In Johnny, the filmmakers took a character previously only thought of as an unlikable bully and humanized him in a staggering way. More than up to the task, Zabka was afforded the opportunity to do things dramatically with his character that were simply never even up for consideration when he first played him in the original film. But Johnny proved to be the show’s ace in the hole for reasons that extended beyond the complexity of his arc. Cleverly relegating him to a relic of the ‘80s in terms of his attitude and worldview, the filmmakers saw a wonderful opportunity there for terrific comedy in a post-woke era where political correctness sets the norms. In Johnny’s mouth, they were able to put lines and thoughts that would normally be interpreted as thoroughly offensive in today’s more sensitive times. But they got away with it by virtue of using a lovable social Neanderthal such as Johnny as their vessel. Zabka, with his deadpan delivery that also barely masked a simmering contempt, killed every time. For this viewer at least, it made for the absolute best moments of humor in the series. It also would not be a stretch to assume that Johnny may have, at the very least, served as a welcome avatar for those audience members who nowadays resent the need to constantly watch what they say.

Was Cobra Kai perfect throughout its six-season run? Of course not. There were more than a few moments, as early as the third season in fact, where you sensed that the showrunners were starting to run out of steam, and thus resorting to the recycling of some ideas. These usually presented themselves in the form of regurgitated karate tropes or displays of excess violence (though I still maintain that the epic battle royal that broke out inside the high school during the season 2 finale was one of the zaniest and most entertaining moments of television I have ever witnessed). The show’s final season, with its extended 15-episode format, perhaps exhibited more fatigue than any other, in part because the novelty factor had by that point surely worn off. However, the filmmakers were still able to pull it off by sneaking in a few final surprises, but mostly by sticking true to the one thing that guided them throughout the entire run: their unwavering love for the characters. In the end, the fate of practically every single one of them, major and minor, is exactly what we might have expected. And it turns out to be less a case of predictability than one of loyalty, commitment, and a vital understanding of the importance to honor all of the things that informed their respective truths.

It is perhaps a minor spoiler to reveal that in the last scene of Cobra Kai we briefly overhear two men seated at a bar discussing a pitch for a Back to the Future television series. The gentleman in question are Josh Heald and Jon Hurwitz, and the whole cameo is a cute tip of the hat to the beloved era they grew up in, and a bonus for any viewers who actually recognize them. As someone who loves Back to the Future and reveres it probably more so than any other ’80s entertainment property, I have always had zero interest in seeing a continuation of something that already ended as perfectly as that one did. I suspect I am also not alone in that sentiment. That said, should a capable artist who also loves it with a ferocity and passion akin to the ones that the makers of Cobra Kai have for The Karate Kid, I just might be willing to happily embark down that road to a place that, I’ve been told, apparently doesn’t need any.