By J.C. Correa

Rock music enthusiasts (and basically anyone with a faint interest in measuring the pulse of pop culture during the second half of the 20th century) are undoubtedly familiar with the seismic importance associated with Elvis Presley’s 1968 Comeback Special. Along with Queen at Live Aid, The Beatles at Shea Stadium, and Jimi Hendrix at Woodstock, the “King’s” appearance on NBC is widely considered one of the all-time greatest and most iconic live performances in the genre. It certainly at least was the pinnacle of Presley’s performing career, and the reasons for it go way beyond the quality of what Elvis brought to the stage on that fateful evening and are explored in great depth in Jason Hehir’s terrific new Netflix documentary.

Having directed the outstanding mini-series The Last Dance on Michael Jordan and the Chicago Bulls, which was preceded by the equally compelling documentary Andre the Giant about the legendary professional wrestler, Hehir now sets his sights on a figure proverbially larger than both of them. Elvis Presley, for many people of different ages at this point, is likely the most god-like symbol that pop culture ever produced. The fact that his life’s story ended in untimely tragedy only adds to his mythos. But because Elvis has transcended so much for so long, many of us were not even alive throughout the two decades of his performing career, let alone during the airing of his fabled ’68 concert in December of that year.

The program, as Hehir’s film illustrates, represented so many things at once for the venerated singer and his career. Even though to most people, the performance probably best symbolizes the most significant crossroads of Presley’s professional journey; one that divides his story into two chapters: The heartthrob, pelvic-grinding sensation of before and the overblown, glitzy Las Vegas version that followed. In crucial artistic terms, to add an accurate comparison, the juncture was the equivalent of The Beatles’ Revolver album.

Interestingly, Hehir spends the first hour of his 90-minute documentary setting up the stakes by painting a thorough backstory to what led to this momentous event. The director enlists the help of various luminaries to tell the full scope of the drama. These include Priscilla Presley and Jerry Schilling (a close friend of the Presley family); author Wright Thompson; filmmaker Baz Luhrmann, who himself knows a thing or two about the topic by having directed Elvis, the Austin Butler-starring biopic two years ago; famed musicians Bruce Springsteen, Robbie Robertson, Darlene Love, and Billy Corgan; and comedian Conan O’Brien, who dispenses with his usual overt schtick to instead relay opinions and accounts in a somber, almost regretful tone that adds a welcome dose of poignancy to the interviews.

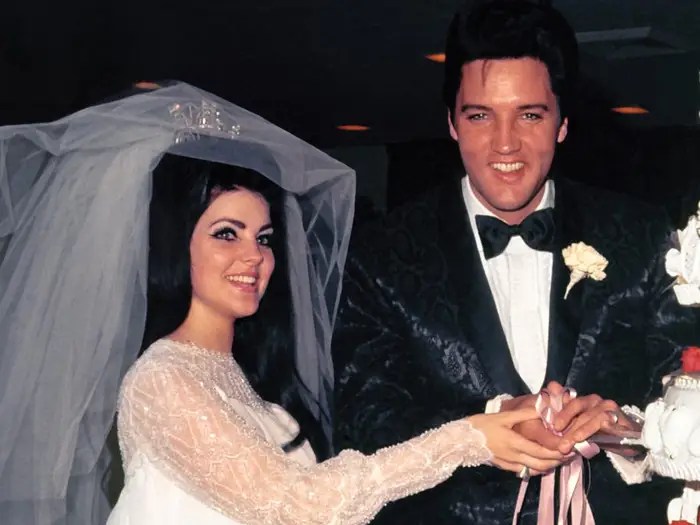

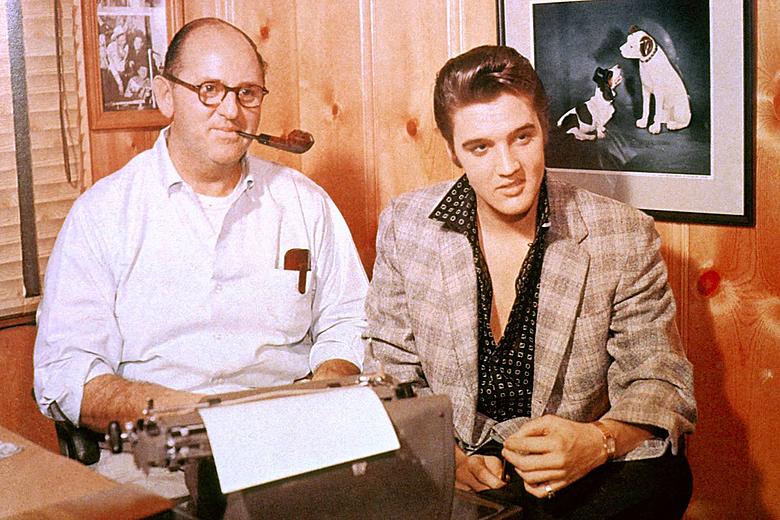

Through the use of much vintage footage and photographs from Presley’s childhood and career leading up to that point, Hehir builds his narrative in a way that leaves us clear about the fact that the seven-year gap that existed between the Comeback Special and his previous performance was not by design, but rather something that frustrated Elvis to no end. His obligatory two-year stint in the army, which began in 1958, was something that the singer privately resented. This, as it turned out, ended up being less of a trap than having been stuck making pictures in Hollywood for the better part of the ‘60s; a move orchestrated by Colonel Tom Parker for no other reason than to further cash in on his golden goose. With a continued barrage of produced scripts that were superfluous at best, this chapter reached its nadir when the “King” hid all his embarrassment while having to sing “Old MacDonald Had a Farm” in one of his movies. Priscilla Presley and Schilling recount this episode in a mortified manner that suggests just how hard of a swallowing of pride this whole endeavor was for Elvis.

Elsewhere however, Love points out that Presley’s heart was in Gospel music more than anything else; a revelation that perhaps some fans may not be fully aware of. As such, we are not so surprised to learn that he received as much artistic acclaim for his recordings in that field as for the way in which he revolutionized rock and roll. In a telling snippet, Corgan states that Elvis “made the genres bend to him, not the other way around.” That thought is also echoed by Springsteen, who goes on to say that for Presley it was important to actually be himself while breaking the rules in the process. Who Elvis really was, it turns out, is a deeply insecure performer and man, and Hehir revisits that theme countless times throughout his feature.

The documentary’s narrative eventually leads us to the elusive Comeback Special and spends its last third covering it. By this point we are fully aware of not just how much was at stake for Presley, but also of the many obstacles in his path. One of the more significant of these was the recognition that Elvis made a name for himself in the ’50s with the music of that time, which was a far cry from how much the rock genre had evolved by 1968, not to mention the importance of the cultural forces that had prompted that revolution. In other words, it was a very risky move on Presley’s part. But like all good stories – and this most certainly is one of the best – when the hero is in his prime and ready to take on the challenge, we better have seatbelts ready to buckle. If Elvis: The Comeback Special indeed represents the artist’s prime, consider then that Elvis Presley was only 33 years old at the time.

As it turns out, that night had its fair share of challenges that went beyond Elvis trying to reestablish his brand. Unsurprisingly, Colonel Parker once again came close to sabotaging his client’s efforts by insisting that the program also include dopey, tangential segments that took the focus away from Presley and his guitar. The documentary highlights the fact that Elvis was genuinely annoyed whenever the proceedings called for him to engage in anything other than music. Thankfully for him and the audience, the “King” had it done his way in the end. No moment is more indicative of the importance of this than the actual opening of the telecast, which sees Elvis singing “Trouble” in dramatic close-up straight into the camera. It is a cathartic instant by any and every measure.

Of course, knowing how his life’s story ended adds an inevitable tinge of melancholy to watching the triumph on display that is essentially the purpose of the aptly titled Return of the King: The Fall and Rise of Elvis Presley. With regards to showbiz stories, as O’Brien reminds us during his interview, “The real great ones have three acts.” Presley’s is most definitely the foremost example of that, with his third chapter being the aforementioned Vegas period, one that also sadly led to his drug dependency and eventual demise. In spite of all that however – or perhaps because of it – Hehir’s aim with his picture is to make Elvis go out on top. Had Presley actually retired after the 1968 performance, it would have been a swan song for the ages, perhaps the greatest in history. But that does not take away the fact that, as the film shows us, on that night at least, he looked like a god. A god that was funny and was also clearly having fun. The overall and most important effect of that evening was instilling the sense for everyone who watched that he never really went away, and that all the many who followed in his footsteps were merely disciples of the actual “King.” A king who, in his endearing, natural insecurity, still felt the need to ask the crowd, “How do you like it so far?”

Return of the King: The Fall and Rise of Elvis Presley is now streaming on Netflix.